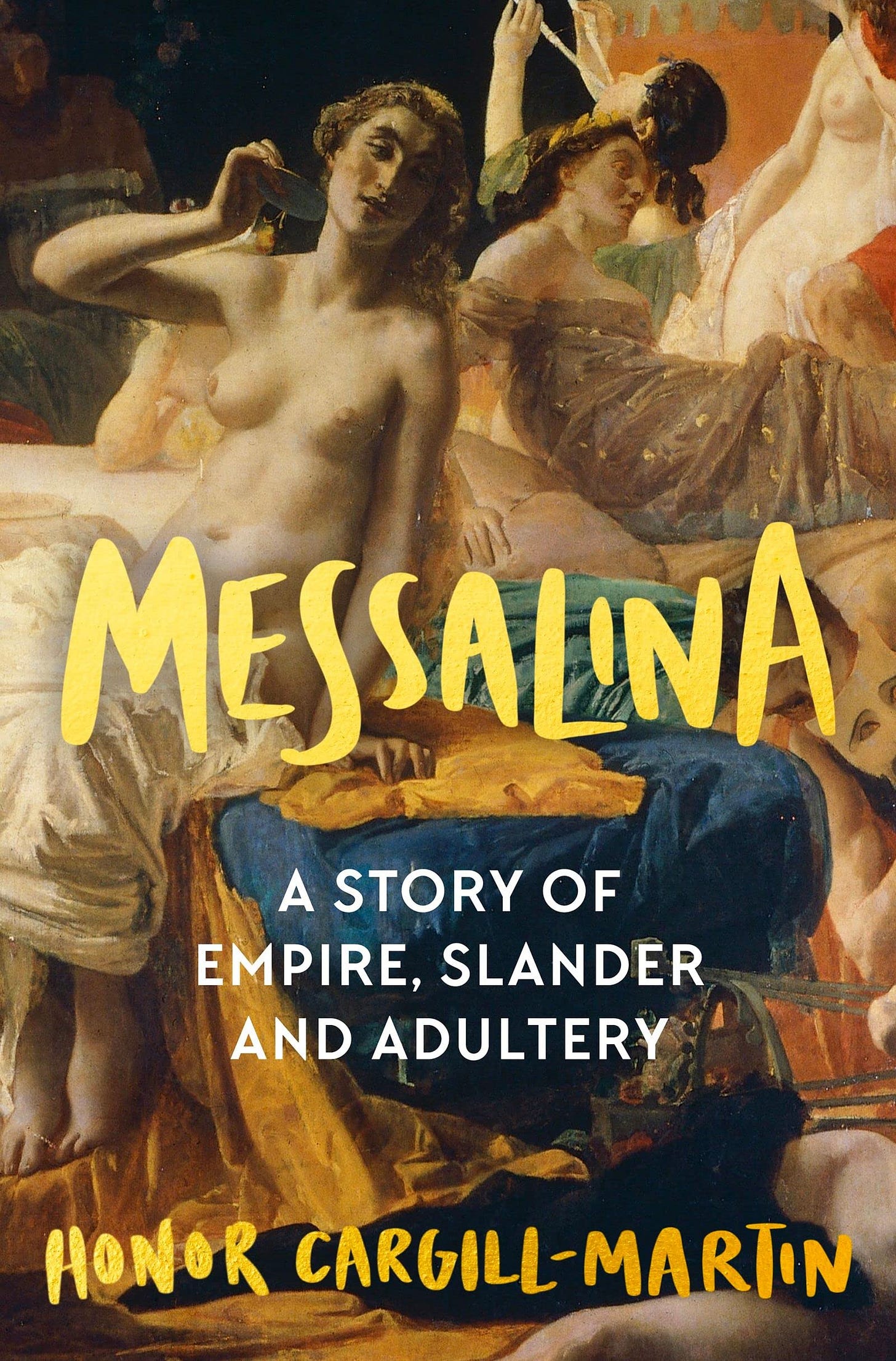

Messalina

A sneak peak of the opening of The Sunday Times Book of the Week - 'Messalina: A Story of Empire, Slander and Adultery' - my biography of Rome's most notoriously badly behaved empress...

‘And so the House of the Princeps had shuddered...’ Tacitus, Annals, 11.28

The story of Messalina’s fall, as Tacitus tells it, goes something like this.

The wedding procession, winding its way through the imperial palace on the Palatine, was in full swing. The year ad 48 had already reached early autumn but evenings in the city of Rome were still balmy enough for outdoor celebration. The bride was wearing the traditional yellow-red veil, choruses of men and women sang songs to Hymen, the god of marriage, the witnesses were assembled, the guests were fêted and feasted. No expense was spared; this was a wedding party for the ages.

It was unfortunate, then, that the bride was already married. And it was particularly unfortunate that the man she was already married to was the supreme ruler of the vast majority of the known world. Entwined with the handsome young noble and consul-elect, Gaius Silius, on the garlanded marital couch, lay Messalina, empress of Rome and the lawful wife of Claudius, emperor of a territory stretching from the island of Britain to the deserts of Syria.

Messalina and Silius had hardly been subtle in celebrating their love, and this in a city where, as Tacitus puts it, ‘everything was known and nothing was kept silent’. Nowhere was this inborn Roman impulse towards gossip more pronounced than in the sprawling, opulent and ruthlessly competitive imperial court where, since its inception some eighty years before, rumour and scandal had always been matters of life and death. And already, as Messalina and Silius slept off the wine and the sex, messengers were riding out of the Porta Trigemina, taking the Via Ostiensis south-west heading for Ostia.

In the mid-first century ad, it was the port city of Ostia that kept Rome running. About fifteen miles south-west of the capital, it was here that every day legions of workers unloaded the cargoes that had arrived from across the Mediterranean and beyond, packing them high on barges headed up the Tiber towards the thronging city and its 1 million consumers. It was through Ostia that rich Romans got their hands on pearls from the Gulf of Persia, Spanish silver, perfumes from Egypt, spices from India and Chinese silks. These luxuries had made the city and its merchants incredibly rich, but there was a more important trade at work too – one on which the emperor’s crown, his life even, might depend.

It was concern for the corn supply – arriving via the great trade route that allowed a million Romans to feed off the flood plains of Egypt – that brought Claudius to the port city this particular autumn. He was to review the logistical arrangements and preside over sacrifices designed to ensure the safety of the ships leaving Alexandria laden with the cargoes of Nile Delta grain that would keep the urban populace adequately fed and politically amenable over the winter. Rather than appear by her husband’s side as First Lady, the empress Messalina had pleaded illness and remained in Rome.

The messengers arriving at the gates of Ostia carrying news of Messalina and Silius’ ‘wedding’ did not dare approach the emperor himself. ‘Don’t kill the messenger’, after all, becomes more of an entreaty than an idiom when the recipient controls the greatest army on earth and the message is that his wife is in the process of marrying someone else. Instead, the messengers went straight to his advisors, Callistus, Narcissus and Pallas. Former slaves of the emperor who had risen meteorically to become Claudius’ closest and most powerful political confidants, they were among the most successful players of the game of court politics Rome had ever seen.

The news presented the imperial freedmen with a serious problem. If Messalina had celebrated a marriage so flagrantly, the freedmen agreed, there could be no doubt as to her next move; the lovers had shown their hand to such an extent that this could only be the beginning of a coup. Gaius Silius was the kind of man who could be emperor. He was as blue-blooded as they came, with charisma and noble good looks and an intelligence honed by the best education money could buy. The political game was one Silius could and would play: he had already been selected to hold the consulship the very next year. Messalina, they guessed, planned to overthrow Claudius, have Silius adopt her son Britannicus, and install her lover on the imperial throne. This was no mere affair; it was a conspiracy to overthrow the emperor – if Claudius was to be saved, Messalina would have to go.

But how could the news be broken to the emperor? Claudius’ advisors knew Messalina had a hold over him; everyone did. The ageing emperor was quite evidently as infatuated with his young wife as his young wife was with Gaius Silius. If he saw her, the game was up; Claudius could on no account be allowed to hear his wife out. The more the advisors discussed the issue, the clearer it became to them that, however strong the case against Messalina, her downfall was not guaranteed. Pallas excused himself, Callistus counselled caution and delay, which amounted to much the same thing. So the task of devising a way to inform Claudius of his wife’s betrayal fell to Narcissus. He had to act fast. Messalina, he decided, could receive no forewarning of the accusations against her. But from whom were those accusations to come in the first instance? Not from him, of course – he had far too much to lose.

Instead, Narcissus recruited two of Claudius’ favourite mistresses, Calpurnia and Cleopatra. (Love for his wife had, perhaps unsurprisingly, done nothing to induce the world’s most powerful man into monogamy.) Hearing the rumours of his wife’s treachery from two of his mistresses would, Narcissus hoped, soften the blow to the emperor’s pride. Having Calpurnia and Cleopatra make the first move would also buy the freedman precious time to gauge Claudius’ reaction before he got his own hands dirty. In return, Narcissus suggested, the women need only think of the gifts, the opportunities, the influence, the power and position even, that they might have to gain from the fall of their lover’s wife. The irony of using two of a husband’s mistresses to accuse his wife of adultery, Narcissus safely assumed, would be lost on Claudius.

Calpurnia and Cleopatra had little difficulty wangling a private audience with the emperor. As soon as the three were alone, Calpurnia threw herself crying at Claudius’ feet, and declared that Messalina had married Silius in Rome. The emperor turned in disbelief to Cleopatra, who nodded and told him, as arranged, to call for Narcissus. The freedman was shown in and confirmed that the rumours were true. He told Claudius that everyone had witnessed his wife’s wedding – the people, the Senate, the soldiers – and that unless he moved quickly his wife’s new husband would hold the city.

Claudius summoned his advisors. The council descended into chaos as courtiers – each with competing interests and significant amounts to lose – shouted over each other. It quickly became clear, however, that the council was seriously concerned about the situation and deemed the threat to Claudius’ rule to be potentially existential. They agreed there was no time to waste and that the emperor should go straight to the army. His position with the elite Praetorian cohorts was crucial – as the only soldiers encamped within the city bounds of Rome they maintained order and had the power to make and unmake emperors. Personal revenge could come later, when the loyalty of the army was certain and Claudius’ position was secure.

Claudius was overcome with panic. He is said to have asked again and again if Silius was still his subject and if he was still in control of his empire.

Back in Rome, Messalina and Silius were still partying. Autumn had reached its mellow height and they were celebrating with a new level of extravagance and debauchery. The palace was filled with wine presses, each churning out steady streams of wine, replenishing the overflowing vats faster than the empress’ guests could empty them. The attendees had come dressed as bacchantes – the wild followers of Bacchus, god of wine – in vine garlands and animal pelts. And they were behaving like bacchantes too, out of control, performing ecstatic dances and leading raucous choruses of rhythmic chants.

Messalina appeared as their ringleader, her dark hair flowing down over her shoulders, with Silius by her side, wreathed in ivy and wearing the laced buskin boots worn by actors in ancient tragedies. This addition to his costume was an apposite one considering the turn that events were about to take.

The wine, the drink and the late autumn heat must have been a heady mixture; at one point during the night Vettius Valens, a famous doctor and one of the empress’ ex-lovers, climbed out of the throng and up into a tall tree. The city of Rome and its surrounding hills and countryside stretched out below him, all the way to the coast. As he clung to the upper branches, the crowd below clamoured to know what he could see. It was funny, he said, but it looked like there was a terrible storm brewing over Ostia.

It was not long before the nature of that storm revealed itself. Despite Narcissus’ orders that the empress should hear nothing of the charges against her, messengers began to arrive from Ostia carrying reports that Claudius knew everything, that he was already on his way, that he was bent on retribution. The party broke up; the guests were falling over each other to leave, to distance themselves as much as they still could from the confrontation that was about to occur. Messalina and Silius departed too: he went straight to the forum to attend to his public duties and show his face as though nothing were wrong; she sought solace in the so-called Gardens of Lucullus on the Pincian Hill, which had recently come into her possession.

Centurions, meanwhile, had arrived at the palace and any party guests who had lingered or tried to hide were arrested. When the news that her associates were being rounded up reached Messalina, she sprang into a frenzy of action. She sent word that her children by Claudius – Claudia Octavia, aged about nine, and Britannicus, nearly eight – should go straight to their father. She also recruited the Vestal Vibidia – the most senior of the virgin priestesses who tended to the symbolic hearth fire of the empire and enjoyed extraordinary powers of legal intercession – to plead her case with Claudius.

Finally, Messalina herself set out on foot across the city, accompanied by just three loyal attendants, suddenly isolated among the teeming urban crowds. She was certain that if she could just see her husband – or, perhaps, if her husband could just see her – the situation would be resolved. Reaching the city gate, the empress hitched a ride on the only vehicle that would take her and set out for Ostia on the back of a cart of garden rubbish.

To be continued…

To discover what happens next (spoiler alert, it doesn’t end well for Messalina) grab a copy of Messalina: A story of Empire, Slander and Adultery from any good bookshop or from the link below. You’ll love it, it’s fantastic, I’m totally unbiased and I promise.

Just finished it about a month ago and I found it so captivating ❤️ I can’t tell you just how much I learned

On my to buy list.

So how fair was I, Claudius and its sequel to Messalina?