Come and Take Them: The Battle of Thermopylae and the making of a political myth

A disastrous defeat, dinner in Hades, and a foundational myth for the West.

In 480 BC, in a narrow pass known as the ‘Hot Gates’, a federation of small cities on the edge of civilisation suffered a crushing and predictable defeat. The defensive force, hampered by strategic miscalculations and hollowed out by desertion, held out for only three days. The super-power they’d hardly dented marched on, into the heartland of the Greeks.

This is how clash of the Greeks and Persians at the battle of Thermopylae might have looked to an objective contemporary observer. A man not hampered by Greek patriotism or blessed with the benefit of hindsight.

Yet, Thermopylae clearly was not a great Persian victory, not in any real sense. In the months that followed, as the Greek dead were buried and the Persian army moved towards Athens, it became a rallying point for Greek defiance. Uniting the fractious Greek coalition and romanticising the sacrifices resistance entailed, it played a significant role in laying the groundwork for the victories at Salamis and Plataea which would drive back the swell of the Persian invasion.

The power of the story has hardly abated in the two and a half intervening millennial. And the formula of its construction tells us a great deal about how we generate our political mythology in the West.

The Cause:

In the late 480s, news of two ominous engineering projects had reached the Greeks: Xerxes, king of Persia, was cutting a canal through Athos and building a bridge of boats over the Hellespont. Behind these new passages of entry from Asia to Europe, troops were mobilising. Xerxes was preparing for a full-scale invasion of the Greek mainland. His aim was not in doubt. The Greek cities of the Ionian coast already paid taxes and swore fealty to the Persian King of Kings.

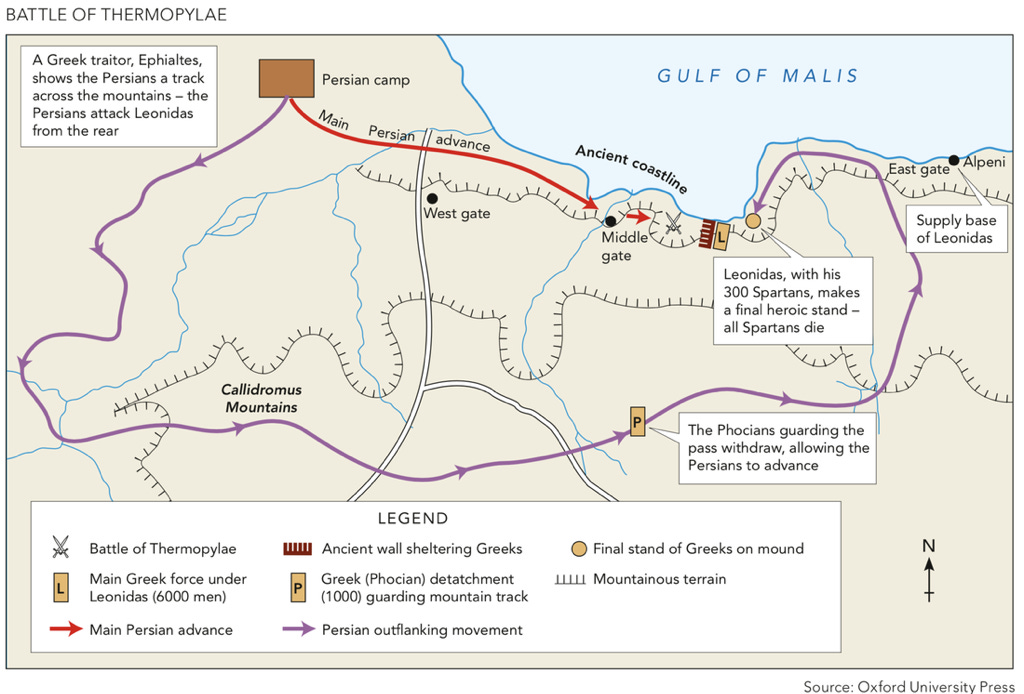

Thermopylae, the most defensible point on the route that would bring Xerxes’ invasion-force into central Greece, was the first and best chance to halt it.

The battle, as it appears in the Greek histories, was an existential struggle of the type most easy to mythologise. A clash of values: resistance and collaboration, glory and subjection, tyranny and freedom.

To many Greeks, the situation would not have seemed so clear cut. The Persians required tribute and symbolic submission, but they otherwise imposed little on the lives of their subjects: no state religion or language, the lightest touch in central governance. It could easily have been argued that resistance was a futile exercise in ego. Many Greeks - both individuals and states - had already willingly seceded to the Persian side.

But there were men among the Greeks, most notably in Athens and in Sparta, who really did see this as a war of irreconcilable moral principles. Herodotus records a conversation between a Persian satrap and two Spartan ambassadors. Why resist? The satrap presses. The Persian king rewards men of worth. Ally with him and he could make them masters of all of Greece. The Spartans counter that the satrap’s advice rests on ignorance. “You know well how to be a slave,” they tell him, with characteristic Spartan candour, “but you have never tasted freedom, and you do not know whether it is sweet or not. Were you to taste it, you would counsel us to fight not with only spears, no, but with axes.”

Thermopylae played a crucial role in entrenching the stance of these men - concentrated in a minority of the seven-hundred or so politically independent, culturally diverse, and usually warring states that made up Hellas in 480 BC - as the stance of all the Greeks.

In doing so, it became a foundational myth for Western culture. At Thermopylae, perhaps for the first time, the Greeks cast themselves as a people defined by freedom - and duty-bound to protect it. The West presents itself in similar terms today; no matter the fact that the ancient Greek concept of freedom does not, as we shall see, map directly onto our own.

The Heroes:

Perhaps seven thousand men fought on the Greek side at Thermopylae. That we remember it as the struggle of three hundred Spartans against the massed forces of the Persian empire is testament to how quickly and effectively the mythic qualities of the story were drawn out.

Myths need heroes. Here - in the three hundred picked Spartans led by King Leonidas - was a group small enough for the imagination to latch onto.

Sparta - a place which seemed extreme even to contemporary Greek observers - had always had a legendary, almost inhuman, quality to it. At seven, boys entered state military training, living in miniature battalions and practicing for war; even after marriage, young men ate in their barracks and visited their wives in secret. All personal desires were subjugated to the strength of the whole; the entire structure of the Spartan state was designed to ensure the single-minded pursuit of martial valour.

Then there were the conditions under which the three hundred Spartan champions had been chosen. These men were picked for their exceptional bravery and skill, but it was also required that they have a living son. The implication was clear: everyone knew it was more than likely that the three hundred would not return.

At the head of these men stood the Spartan king, Leonidas. Having ascended to the throne unexpectedly after the death of two older brothers, he had emerged as an ideal Spartan ruler: pithy in speech and fearless in war. He traced his lineage back to Heracles and later writers would call him the equal Achilles.

Leonidas emerges from the historical tradition as a man entirely willing to die for his country and his cause. A later version of the story has him summarise succinctly his unclouded understanding of the mission. When asked why he was taking such a limited force, he replied that his troops were indeed few to hold the pass, but that they were numerous for their real purpose - death. "Officially,” he said, “I lead my men to defend the passes, but in reality, I lead them to die for the freedom of all.”

It was said too that Leonidas had a more personal motive for self-sacrifice. The Spartans had received an oracle from Delphi that warned a Spartan king would need to die to ensure the survival of the state. At Thermopylae Leonidas seemed determined to be that king.

The best three-hundred fighters, from the best fighting state in Greece, led by a heroic King on a selfless suicide mission. There could be no better symbol of resistance.

The Villains:

As the Spartans became perfect heroes, the Persians were transformed into perfect villains.

Contemporary Greek culture painted the Persians as cowardly and effeminate, men better suited to slavery than to freedom. It was said their bodies were softened by Eastern luxury, their minds weakened by total subservience to the King of Kings. There were reports that Persian troops had to be driven into battle with whips.

This characterisation seems strange for men who had conquered the greatest empire the world had ever seen. The Persians were as deeply concerned as the Greeks with honour and strength - and they had put these values to more magnificent use. Key to the Persian honour code was a distinction between the ‘Truth’ and the ‘Lie’; the former representing order and the latter chaos. The mastery of the troublemaking Greek states would have been viewed in the Persian capital at Susa as a mission to impose the stable, righteous Truth of Persian rule onto the anarchic and seditious Lie that festered on their borders in Greece.

They had been imposing such order across the Near East for the past seventy years. These conquests meant the Persian king could call on a vast reserve of conscripts, but at the core of his army stood an elite force of Persian infantry. Ten thousand-strong, and known to the Greeks as the Immortals, these men were just as highly trained and just as prepared to die for their country as any Spartan.

All the evidence was stacked against a characterisation of the Persians as effeminate weaklings, but nonetheless it became ingrained in Greek thought. In this too Thermopylae would play a crucial role. The details of the battle - after some bending, perhaps - lent themselves perfectly to Greek propaganda.

The Struggle:

Thermopylae was fought over three days in August. At its narrowest, the battlefield - crushed between the mountains on one side and the sea on the other - was perhaps 20 or 30 meters wide. Leftover leaves from the previous winter were dry and crisp underfoot. The heat was so bad that one Spartan quipped it was a good thing the hail of Persian arrows was thick enough to blot out the sun - it meant they could fight in the shade.

For two days, the Greek forces held out well against the Persian onslaught. The conditions were entirely to their advantage.

The Persian army had been developed to be lethal on open plains and rugged plateaus. Its great strength lay in the speed, range, and mobility of the troops - but these qualities meant nothing without space. With their archers and horseman severely constrained, the Persians were forced into an infantry clash with the Greeks.

Close-combat infantry fighting was where the Greeks excelled. Their hoplite soldiers, armed with heavy round shields and two-to-three meter-long spears, were unwieldy but deadly. These men fought in a formation known as the phalanx: lines of hoplites stood shoulder-to-shoulder, their shields overlapping to create a solid wall broken only by protruding spears. These lines, stacked eight or so ranks deep, pushed forward as one coherent mass into the enemy.

Along the narrow front at Thermopylae, the Persian numbers meant nothing. Any troops sent forward were butchered by a seemingly unbreakable Greek line. Three times on the first day of fighting, the Greek historian Herodotus tells us, Xerxes leapt from his throne in fear for his army.

The very nature of the hoplite phalanx played into the idea that this was a clash of values. All hoplites were citizen men, and the phalanx relied on their total unity and co-operation. “Fighting singly,” a Spartan defector is said to have warned Xerxes, “Spartan soldiers are as good as any, but fighting together they are the best in the world.” It was as though the Greek city-state ideal itself was beating back the great, diverse throng of the Persian army.

The Crisis:

It was towards the end of the second deadlocked day that things changed. According to the Greek sources, a local man named Ephialtes presented himself at the Persian camp. He was taken straight to the King of Kings.

Ephialtes told Xerxes he knew of another path. A route that would circumvent the pass entirely, taking the Persian troops up through the wooded mountains and spitting them out behind the Greek forces.

It was a treachery, Herodotus claims, motivated entirely by Ephialtes’ hope of rich reward from the Persian coffers.

Xerxes acted on the intelligence at once. His Immortals set out just as the lamps were being lit in the camps. They walked all night, emerging on the hill above Thermopylae at sun-rise.

The Greeks had been well-aware of this alternate route and Leonidas had stationed a small force of local volunteers to guard its end. These men, undertrained and woefully outnumbered, fled under the first volley of Persian arrow-fire.

News of the Persian arrival, meanwhile, reached the Greek camp, borne by messengers streaming downhill from the lookout posts. It was clear that defeat was now both inevitable and imminent.

As dawn broke, Leonidas sent away most of the Greek troops. Perhaps, as Herodotus claims, he was uncertain of their resolve; perhaps he wished to preserve as many Greek units as possible from the coming massacre. The Thebans and Thespians were to stay, and so too, of course, were Leonidas and the Spartans. Herodotus claims Leonidas felt it would not do to desert his post, but he must also have known that the other Greeks would need cover for their retreat.

No point remained in holding the line. Instead, Leonidas and his men fanned out. Their only aim now was kill as many Persians as possible. They did so: fighting with their swords once their spears had been broken, until, Herodotus claims, “no one could count the number of the dead”.

The Greeks, Leonidas among them, were slaughtered to a man.

It was a disastrous defeat. The Greeks - in part due to Leonidas’ miscalculation in defending the alternate route so lightly - had lost their best line of defence against the Persians. The road to mainland Greece now lay open before Xerxes. Within a month, Athens would be burning.

The seeds of Thermopylae’s recasting, however, lay in the very method of Xerxes’ victory.

The Persians, the Greeks argued, had triumphed only because of one man’s treachery. The Amphictyonic league placed a public bounty on Ephialtes’ head and the story that he had been motivated by pure and personal greed swiftly became fixed.

The reality was perhaps more complicated. Ephialtes’ defection could well have been ideological. Many of his compatriots had already gone over the Persian side and, as the Athenians and Spartans talked of freedom, Xerxes’ troops, held up behind the pass, were harrying local farms and drinking rivers dry.

Nor would the Persians necessarily have needed Ephialtes at all. The vast variance of the terrain covered by the Persian empire had made them expert in reconnaissance and adaptation. There is no reason to assume they would have simply waited helplessly for Ephialtes’ deliverance. Persian scouting and the proactive use of local intelligence would likely have laid open the alternate path before too long.

The narrative of Ephialtes - one single, venal traitor - suited the Greek agenda. Thermopylae became a glorious tale: the story of a global superpower, forced to rely on treachery and resort to ambush to secure an unmanly victory against a out-numbered cadre of loyal and fearless heroes.

The Slogan:

The tale of Thermopylae - of the three hundred; of Leonidas, Xerxes, and Ephialtes; of the heroic last stand and the inglorious Persian victory - took hold of the Greek imagination.

The story’s constant use and reuse can be traced in the development it undergoes over the centuries that follow. By the first-century BC, the version we found in Herodotus has been embellished. There are new, almost filmic scenes. There is a secret Spartan mission to assassinate Xerxes. And, perhaps most importantly of all, there are the slogans.

In these accounts, a striking number of quotes are attached to Leonidas’ name, many of them - “eat as though you’ll dine tonight in Hades!” - juicy enough to be transcribed almost verbatim by Hollywood executives two millennia on.

Laconic, audacious, and darkly humorous in the face of death, the sayings attributed to Leonidas are testament to the hero cult which had grown up around the Spartan leader. Testament, in other words, to the success of the process of myth-making which had begun in Thermopylae’s immediate aftermath.

The most famous of the lines associated with Thermopylae is perhaps ‘molon labe’. A Greek phrase meaning “come and take them”, this, the later sources claimed, was Leonidas’ response to a message from Xerxes demanding he lay down his arms.

The appeal of its provocative defiance is obvious; just as it roused the ancient Greeks, it has become a rallying point for pro-gun, anti-government movements on the American far-right.

Their use of the phrase, however, rests on a misunderstanding of the Greek - and especially the Spartan - definition of freedom.

Freedom, for the Spartan citizen, meant the right to participate in the governance of the state and the freedom of that state from foreign intervention. There was no sense that the citizen himself ought to be free from the intervention of the state. Quite the opposite: there was no aspect of what we would now term ‘private life’ into which the Spartan state did not intrude.

When the Spartans refused to lay down their weapons in the fight for freedom, they were fighting not for the freedom of the individual, but for that of the collective.

Thermopylae - an object lesson in the generation of political myth - is often cited as the first iteration of a long struggle for Western civilisation. Its binaries, however, are not so simple, nor its driving values so transferable to our own age as the accretion of two-millennia worth of rhetoric would have us believe.

I'm a huge fan of how elegantly you pack a lot of information in a small amount of words.

Thanks for mentioning the many other Greek soldiers who were there. I've heard that the Spartans shoved the helots up front as fodder. Also, how many people ever give the Athenian fleet any glory?