Ancient History Field Notes vol. 1

Alexander the Great, the ex-slave behind Sallust, and an extraordinary feat of Roman craft.

Where do we keep the information we discover?

Everyday I come across new things that fascinate me about the ancient world. Anecdotes, cultural quirks, quotes, archeological stats, snippets of writing, etymologies, works of art, stories about people you’ve never heard of before and probably never will again.

These things aren’t relevant to my doctoral dissertation — but they appeal to me. They are the debris of the complicated cultures and real lives of the ancients. Let them pile up and over time you get a much truer, fleshier sense of the Classical World.

Collecting these miscellanies has been one of the great joys of being at the University of Oxford and working on my doctoral project. I spend every day reading, talking to people cleverer than myself, and listening to the greatest living experts tell me about things they’ve studied for decades — in the process, I collect more and more of these satisfying puzzle pieces about the past.

But what to do with them.

In the Renaissance people kept commonplace books, but I’ve never managed to hold on to a notebook for more than two weeks. Sometimes I take photos of my computer screen, but it’s just too uncivilised.

So, this is my new plan — Field Notes. A collection of the compelling things I discover in my research. As wide ranging as possible. Things you might not read about in history books, but which might fascinate you, delight you, spark a thought, or give a new dimension to your understanding of the past.

This week, we have an Alexander the Great anecdote, the life-story of a Roman slave turned literary star, and one of the most beautiful (and roguishly tempting) pieces of Roman glassware ever discovered.

Alexander the Great vs. Advice

It is the year 331 BC. You are a twenty-five year old king standing on an Iraqi ridge two and a half thousand kilometres from home. You have 47,000 troops to your name. Across the plain are arrayed the massed forces of the Persian empire. This army, led by Darius, King of Kings, is at least double, quite possibly five times the size of yours, and their chariot wheels are fitted with scythes. You have beaten Darius twice before, but on those occasions his force was significantly smaller and the terrain was in your favour — this time it is in his.

This was where Alexander the Great found himself on the 1st of October 331 BC, on the morning of the Battle of Gaugumela. It was a situation that could easily have been avoided. A year before, Darius had sent envoys offering him peace on remarkably favourable terms — they would be allies, and in return Darius would offer Alexander his daughter’s hand in marriage and all the lands up to the Euphrates.

Alexander called a council of his friends and laid the options out before them. He wanted their free and honest opinions — or so he claimed. The only man that spoke up was Parmenion, a great commander who had been Alexander’s father’s most trusted general. “If I were you,” Parmenion is reported to have said, “I would accept what’s on offer and make a treaty —”

“And so should I,” Alexander cut in, “if I were Parmenion.”

With that, the council was concluded, Alexander refused Darius’ terms, and the armies moved closer to their coming reckoning. The risk, as it turned out, paid off. Alexander routed Darius at Gaugumela, breaking through a crack in the Persian flank and pursuing the king himself, whilst Parmenion held the left wing even as it was attacked from the front and side. With this implausible victory, Alexander made himself master of the entire Persian empire.

But is the story of his rejoinder to Parmenion true? As with almost everything about Alexander, it’s impossible to say. The tale fits suspiciously neatly with the characterisation of Parmenion and his coming struggle with Alexander, and it has all the air of the apocryphal about it — but none the less it appeals to me, and I think it captures the heady mixture of confidence, arrogance, and delusion on which extraordinary glories (as well as extraordinary disasters) are built.

Lucius “Lover of Words” Ateius

In the late Roman republic, a famed rhetorician and critic named Lucius Ateius “Philologus” claimed to have written more than eight-hundred books. It was all the more remarkable because the Athenian-born Philologus had come to Rome as a slave.

An expert in literature, philology, rhetoric, and history, it is possible Philologus had been well-educated before he was enslaved. It is more likely, however, that the spark of his intelligence was spotted by his master during the basic education afforded to slaves set for work in the household or in trade. This was something to be cultivated. Highly educated slaves were the most valuable of all, serving as tutors, advisors, and symbols of a family’s intellectual discernment — literal cultural capital.

So Philologus was afforded a higher education, and, when it became evident that he would do for more than a family tutor, he was freed. He could now go about integrating himself into Rome’s intellectual elite. He studied under Marcus Antonius Gnipho — the rhetorician (and fellow freedman) who had taught Julius Caesar — and established himself as a tutor and travelling companion to young aristocrats. He began to write too: a treatise on rare words; a monograph on the question ‘Did Aeneas love Dido?’; in all, he claimed in a letter to a friend, some eight-hundred books on every sort of topic imaginable. It was in homage to this obsessive, wide-ranging pursuit of knowledge that he took the name “Philologus” — a name meaning, quite literally, in Greek, “Lover of Words”.

His work brought Philologus to the attention of the more literary branch of Rome’s aristocracy. First, he fell in with Sallust, a Roman senator on the outs in the wake of a serious corruption scandal and trying to work out what to do with himself. One thing Sallust was considering was history, and so he commissioned Philologus to write a brief survey covering all of Roman history, from which he might select a suitable topic for his work. Philologus did so, and the result was two of the greatest works of Roman history ever written — Sallust’s accounts of Rome’s war with the African king Jugurtha and of the conspiracy and rebellion of Catiline. Ancient commentators beleived they could see Philologus’ hand in the style as well as the content of these masterpieces.

After Sallust’s death, Philologus was quickly picked up by Asinius Pollio. A statesman and general, a partisan of Caesar’s and then of Antony’s, Pollio had held the consulship in 40 BC, celebrated a triumph in 39, and then promptly retired from politics completely to devote himself to the arts. He had used the proceeds of his foreign victories to build Rome’s first public library, organised her first public literary readings, and helped launch the careers of the great Latin poets Virgil and Horace. But he wrote in his own name too — poems, plays, orations, and histories — and it was in this capacity that he wanted Philologus’ help, commissioning the freedman to compose a set of rules to guide his own writing.

None of Philologus’ works survive. But the brief mentions we have are testament to an extraordinary man, to the peculiar ambiguity of Rome’s attitudes to slavery, and to the extreme shifts in fortune possible in the extreme city of Rome.

The Cologne Cup

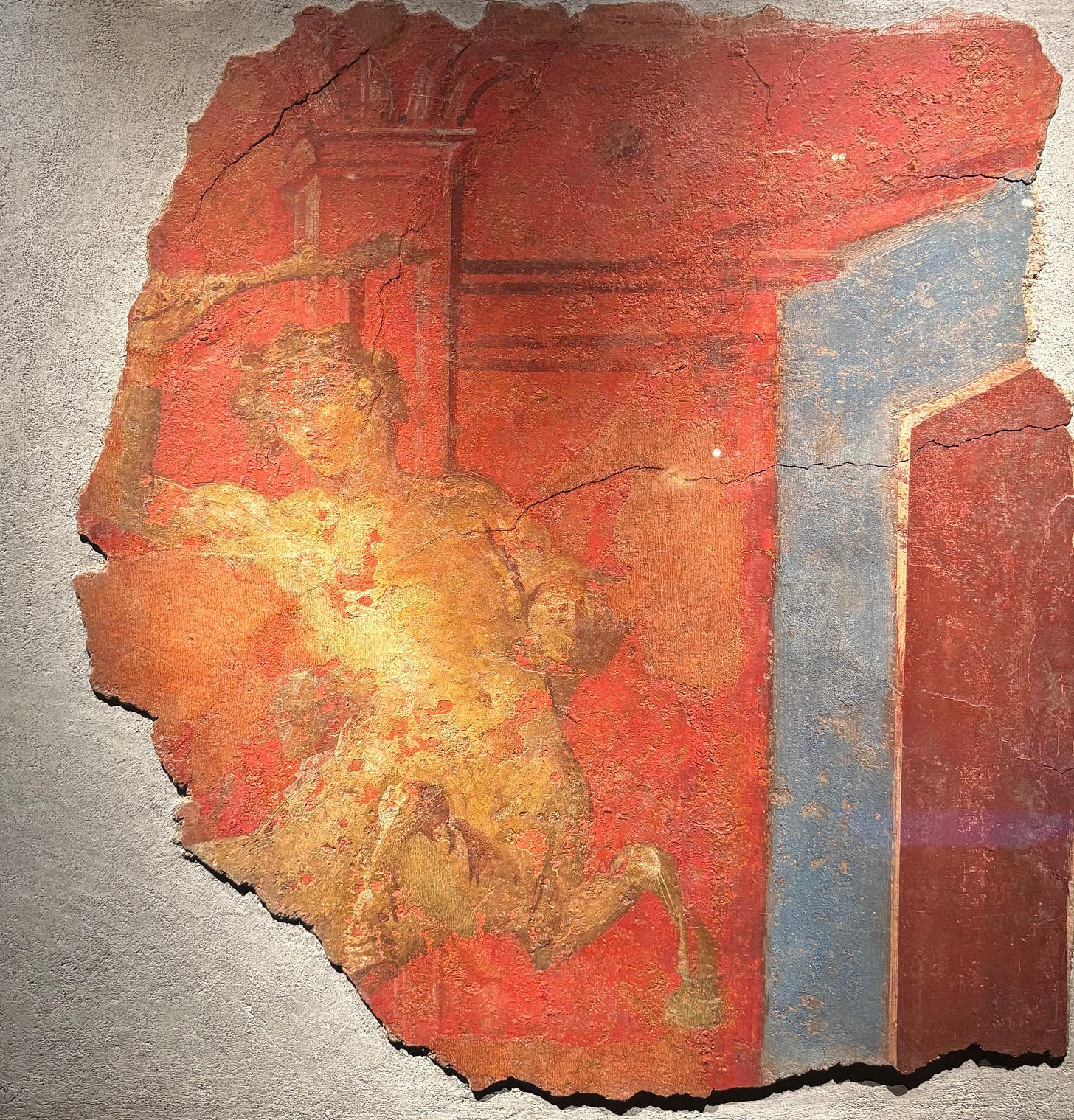

In the Romano-Germanic Museum in Cologne sits one of the most extraordinary pieces of Roman glasswork ever discovered. A ‘cage cup’ or vas diatretum made in the 4th century AD.

The inner layer is a simple cup of fine clear glass. But around it sits an encircling net of lace-like green and gold glass, its attachments invisible so it seems to hover in the air around the cup. The effect is wonderful today but filled with red wine and seen in the lamp-light it must have been better still. Like a cabochon ruby set in gold and enamel fretwork.

My favourite part of all, however, is the inscription beneath the cup’s rim. Made up of ancient greek letters which stand out crisply from the rest of the cup in raised red-purple glass, it reads ‘Drink, live beautifully forever’.

Finally. An order I can get behind.

Love this. As a connected thinker, I believe collecting "miscellaneous" items is a creative way to arrive at innovation. Especially in the anecdotally rich field of the classics. Cf. Herodotus. More please.

Feeling Parmenion's pain - a classic example of a totally awkward moment

Great read as always Honor - I never fail to learn something new from your articles