“Just as our bodies grow gradually and degenerate quickly, so it is easier to crush men’s character and zeal than it is to revive it”

The Emperor Domitian had been dead for almost a year when the Roman historian Tacitus published his first book, the Agricola, in the summer of AD 97. The losses incurred in the course of his tyranny, however, were still being counted.

A lot of good men had been killed and a lot of good books had been burnt. The Senate and magistrates had been stripped of whatever dignity and authority they retained. Fear of Imperial informers had taught men that they could not speak freely even in private.

Now, as the relief that followed Domitian’s assassination wore off, the Romans wondered how much of the political culture they prized — the love of liberty, the citizen-pride, the inborn abhorrence of tyranny which they had always felt set them apart from and above other nations — had survived the years of aberration.

In the opening of the Agricola, Tacitus tells us that he had first wanted to write the book — a biography of his father-in-law — four years earlier, when Agricola had died. There was ample material. Agricola had completed the subjugation of Britain, explored the northernmost reaches of the known world, and pushed Roman dominion to the Orkneys. These were deeds that warranted recording. Doing so would once have been seen as a public duty: the commemoration and emulation of great deeds was the means by which the Romans believed their virtues might regenerate themselves.

But when Tacitus approached the Emperor to request permission to begin the project, Domitian had made it quite clear that such commemoration would not be welcome. There was now space for the commemoration of only one man’s great deeds — those of the Emperor himself. Had he been intending to assassinate Agricola’s character, Tacitus comments bitterly, he would not even have had to ask, “so violent and hostile were those days to virtue”.

So Tacitus laid the idea aside. Things got worse. Two men were executed for writing sympathetic biographies of Thrasea Paetus and Helvidius Priscus — Stoic martyrs who had been killed for refusing to collaborate with previous emperors — and their books were burnt in the forum. Domitian and his hangers-on “evidently believed,” Tacitus says, “that in those flames the voice of the Roman people, the liberty of the Senate, and the conscience of mankind would all be destroyed”.

It seemed a real risk. In contrast to the philosophy-focused Greeks, the Romans believed that people learnt ethics best not through abstract theory but through examples. They needed to see virtue rewarded and read stories of ideal heroes if they were to learn to be good citizens themselves. Rome had carefully preserved a great chain of these exemplary stories, stretching right back to the legends surrounding her foundation — and now Domitian seemed to be severing it.

Tacitus ends the passage on a note of hope. Memory was not so easy to destroy, he says, as books had been. It was easier to be silent about what you remembered than it was to actually forget.

He could not hope, however, that the restoration of Rome’s political culture would be a quick process. “The nature of human weakness,” he warns, “means the remedy is always slower than the disease. And just as our bodies grow gradually and degenerate quickly, so it is easier to crush men’s character and zeal than it is to revive it”. Domitian had been in power for fifteen years and even before he’d come to the throne, the moral integrity of Roman politics had been weakened by the mismanagement and despotism of Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero earlier in the century. A great deal of damage had been done.

Pliny the Younger — orator, writer, statesman, and nephew of the great natural historian — was a direct contemporary of Tacitus’. The collections of letters he published in the early 1st century AD (in which Tacitus appears as a regular correspondent) are ridden with the same anxieties about the invisible ravages left by Rome’s years of subjection.

One problem was that, on the most basic level, politicians no longer knew how to behave.

More than a decade after Domitian’s death, Pliny wrote to his friend Titius Aristo, anxious that he had made a faux pas in the Senate. He was aware that he should know the rules of engagement that governed senatorial meetings, he said, and he was embarrassed that he should have to come to Aristo, an expert on the history of public law, for help.

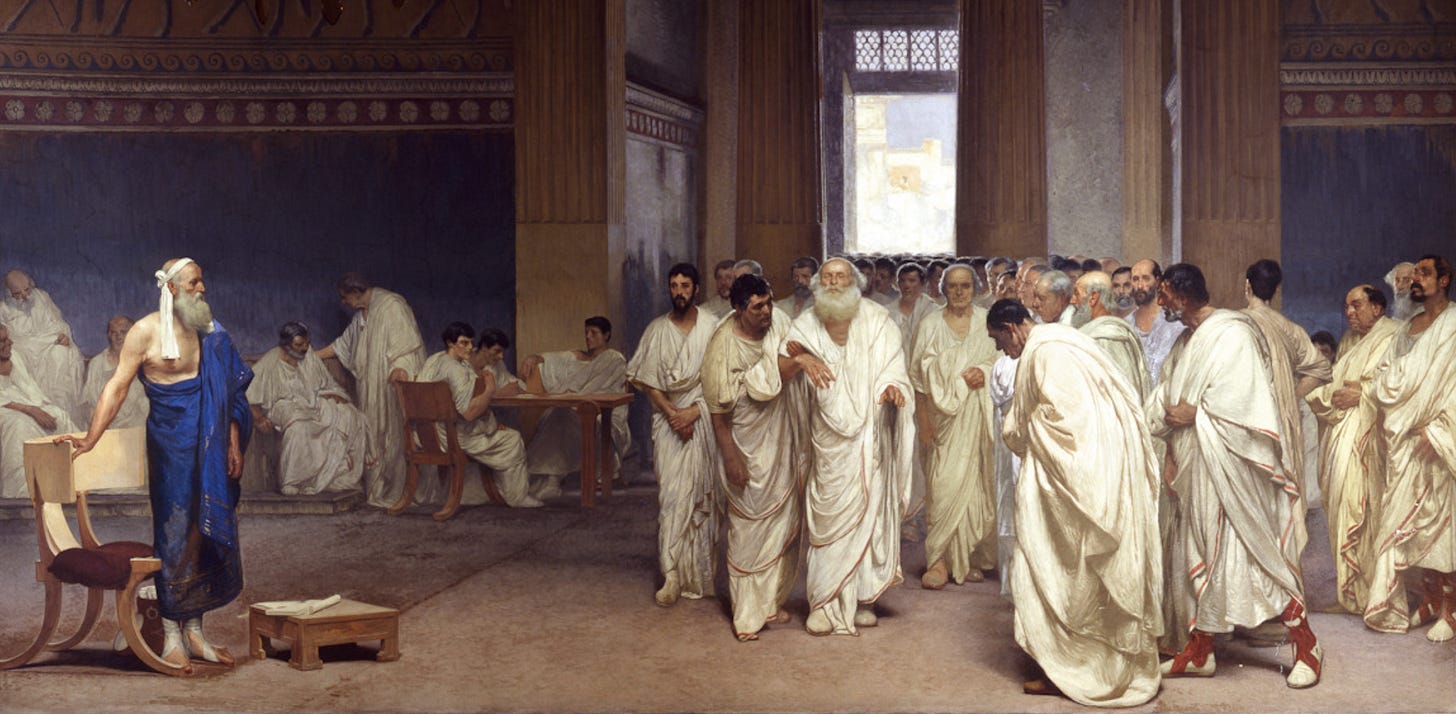

In the past, candidates for public office had stood in the doorway of the Senate House and watched the constant debates, trials, and bill hearings of a body in good working order. They had learnt, by observation and experience, how to do things in a way that maintained the Senate’s culture of rigorous public service.

But Pliny’s generation had not had the advantages of their ancestors. They had grown up observing a Senate neutered of any real power, stultified by the fear of saying the wrong thing, and called on only for the ratification of Imperial crimes. “Now we became bad senators ourselves,” he rued, “and for many years we witnessed and bore participation in the evils. And by this, in the end, our characters were blunted, beaten, shattered.”

There had been a dearth of good examples, and there had been a surfeit of bad ones. One day, a few years before he wrote to Titius, Pliny had noticed a monument he had not seen before on the Via Tiburtina. It commemorated honours that had been granted by the Senate to Pallas, one of the Emperor Claudius’ most powerful freedmen, in AD 52. Pliny was horrified. Here was a man - not a Roman aristocrat but an ex-slave - who had risen through palace intrigues and enriched himself through corruption, being lauded by the Senate. And here was a monument recording those rewards, so that young Romans might learn from Pallas’ example: they too could be offered fifteen-million sesterces straight from the public treasury if they simply laid aside their morals in the service of the emperor.

After such assaults it could hardly be expected that Rome’s political culture would regenerate itself immediately or automatically. The process of repair would have to be a gradual and active one.

In part this would involve political changes, ones the new regime (led first by the short-lived Nerva and then by his co-emperor and heir Trajan) was already enacting by affording the Senate more freedom and responsibility. But perhaps even more critical was the work of rebuilding Rome’s political culture — work in which both Tacitus and Pliny took part.

Despite its Domitianic setting, the Agricola had been a largely positive work. A vision of how “great men can exist even under bad rulers” by laying aside their pride and doing good in those areas, provincial governance for example, where they might make a difference. When Agricola died, Tacitus says, people mourned him sincerely; “you could easily trust he was a good man, and gladly believe him a great one,”

Tacitus’ next historical works were darker: first The Histories, which ranged from the death of Nero to the tyranny of Domitian, and then The Annals, which trained an unflinching eye on the Julio-Claudians. These were autopsies as much as histories; Tacitus sought to isolate the causes of the political malaise from which Rome suffered in these periods and chart their spread through the body politic.

Pliny did something similar. After he wrote the first letter regarding Pallas’ monument, he went back and looked up the senatorial decree it commemorated. When he found that the monument had not done the Senate’s sycophancy justice, he wrote another letter which combed through the original decree, quoting large tracts of it and breaking down the moral corruption it revealed. This was not an easy letter to write — Pliny pictures in unsparing detail just how servile a scene the Senate must have presented as they composed the decree. He blushed for those times, he claimed, as though he lived them.

Like Tacitus’ histories, this letter forced its readers to look — to really look — at their nation’s most humiliating and shameful days. It might be hoped that having done this they would avoid repeating those same mistakes in the future.

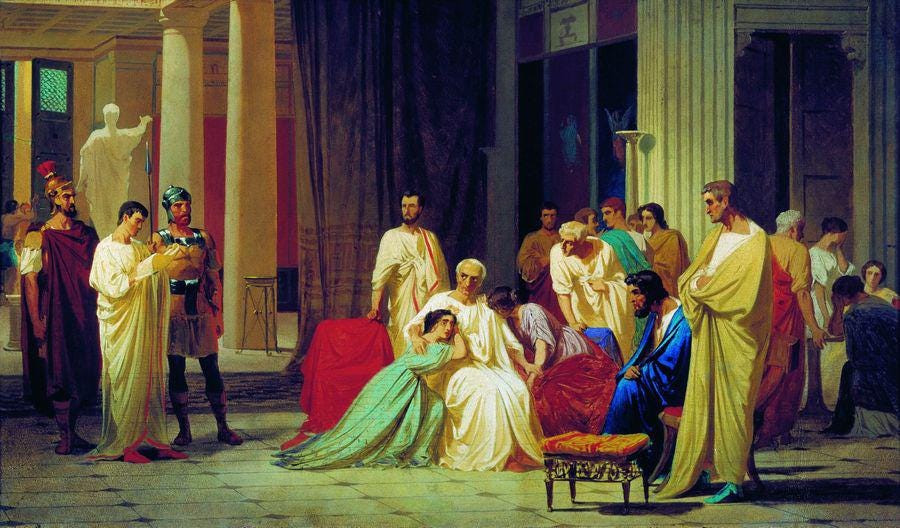

But as well as demonstrations of what to avoid, people needed models to aspire to. Tacitus gave them some in his depictions of men like Agricola and Thrasea Paetus —men who had managed to maintain their integrity despite all the adverse conditions of tyranny. Pliny too, constructed many of his letters around stories of virtues — liberty, loyalty, honesty, resilience, self-sacrifice — displayed by heroic senators, but also by women and by slaves. Often these stories were associated with the households of people Pliny knew; they had been preserved as family stories, it seems, when the political situation had meant that they could not be celebrated openly. Now that times were safer Pliny wrote them up — memorably, moralistically, and often-melodramatically — for the public. These were modern heroes for the new Imperial age, ones designed to spur a resurgence of public virtue to match Rome’s newly settled politics.

When he composed the Agricola, Tacitus had expressed a cautious hope that the new regime would provide enough space and stability for the long work of cultural restoration to begin. His optimism was not entirely unjustified. Nerva and Trajan were the first of Rome’s 'Five Good Emperors’; Rome would enjoy eighty-years of unprecedented stability and relative Imperial toleration before the rise of her next tyrant — the gladiator-aping, ostrich-beheading Commodus.

Oh this is painful. I've never had the courage to read all of Tacitus because of how bleak it is. Previously I could frame this as something a Roman other might do that didn't really apply to our safe, modern, and democratic lives. Now, of course, I see that there's nothing in Tacitus that I couldn't see happening in US politics in another few months or years, and that's disconcerting.

"One problem was that, on the most basic level, politicians no longer knew how to behave."

Wow what a lesson from history. Where are the good political leaders the world so badly needs and what role models are our youngsters to follow.